Stitch Fix: Clients are not Fixated on it

Low barriers to entry, rising CAC, and high churn make scaling difficult

I tried Stitch Fix ($SFIX) for the first time in London. I am by no means a shopper or fashionista, but I decided to give it a shot anyway. After providing the usual measurements and playing their Tinder-like Style Shuffle, I received my first “Fix”, a selection of five articles of clothing. To my surprise, everything looked great, so I kept all the items. But I never ordered a second Fix.

I am guessing I am not the only customer who orders just once and never returns.

Stitch Fix: Data Driven Flywheel

Data science powers the selection engine behind Stitch Fix. Fewer human stylists are involved in the process these days. Back in 2018, here is what founder Katrina Lake had to say about her philosophy and approach to apparel retailing:

“Fit and taste are just a bunch of attributes. It’s all just data.”

In other words, everything is quantifiable, right down to something as subjective as taste. With its direct-to-consumer business model, Stitch Fix collects extensive data from customers and Fixes that it has accumulated since its founding in 2011. Each touch point with a client is an opportunity to collect more, from the initial set of questions one must answer prior to receiving the first Fix, to what items are retained and returned with reasons why. Style Shuffle further teases out what a client likes or dislikes.

All these data points add to the flywheel effect, which allows the company to continuously improve its algorithms and engineer better recommendations.

Indistinguishable Black Boxes: Implications on Competition

Algorithms, however, are invisible. When surveying multiple styling services, it is hard to distinguish one from the other. They all seem to carry similar brands with different iterations. How will prospective customers know whether Stitch Fix, Wantable, or Stately Men will provide a better selection?

Unlike marketplaces like Amazon or Farfetch where customers can comb through available inventory and look for what they want, a styling service only offers a peek. It is the very nature of its business, which is to deliver a surprise to customers on receipt or show an AI-curated assortment.

Perversely, such obfuscation may encourage more new entrants into the market, since they do not need to carry like-for-like inventory upfront to compete with incumbents. Just a promise of delight to customers with a handful of the most popular brands can get a new service in full swing. In the U.K., there are already a multitude of options – including Lookiero, Estilistas, and Try Tuesday by Marks & Spencer’s – competing against Stitch Fix since it launched in May 2019.

Increasing Customer Acquisition Costs

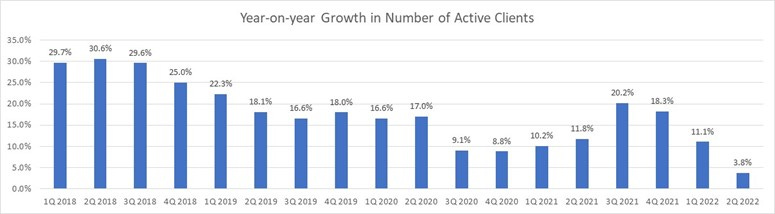

Apart from fulfillment centers and corporate headquarters, Stitch Fix does not have any other significant physical footprint, thereby keeping its overheads low. Their stylists all operate remotely on a part-time basis and are paid by the hour. Management has maintained its declining profitability to be a function of continuing investments in growth. But incremental Active Clients have been slowing down for years, as have adjusted EBITDA margins, indicating an environment of rising customer acquisition costs.

Leaky Bucket: Customer Stickiness is an Issue

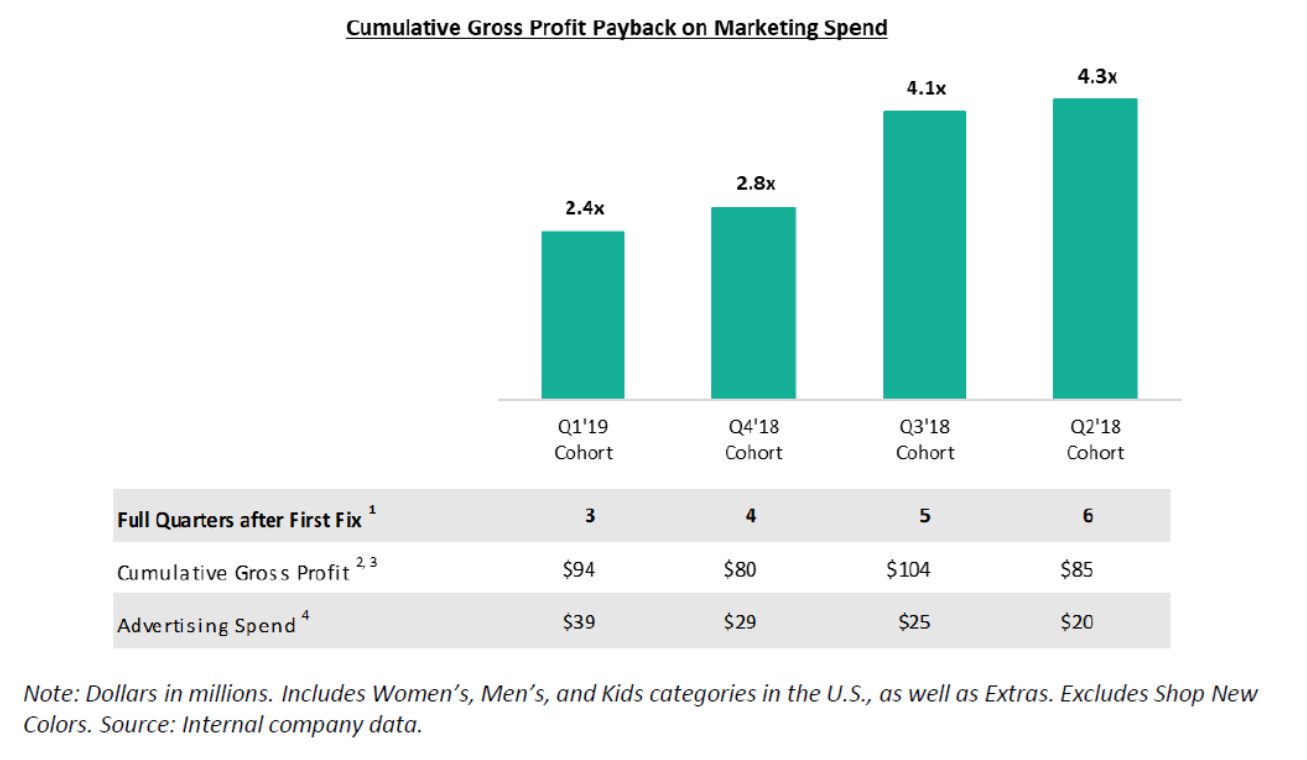

In the Q4 2019 letter to shareholders, Stitch Fix presents its case of high payback on marketing investments by juxtaposing its advertising spend against cumulative gross profits (up to Q4 2019) from each cohort of customers from four past quarters (Q2 2018, Q3 2018, Q4 2018, Q1 2019):

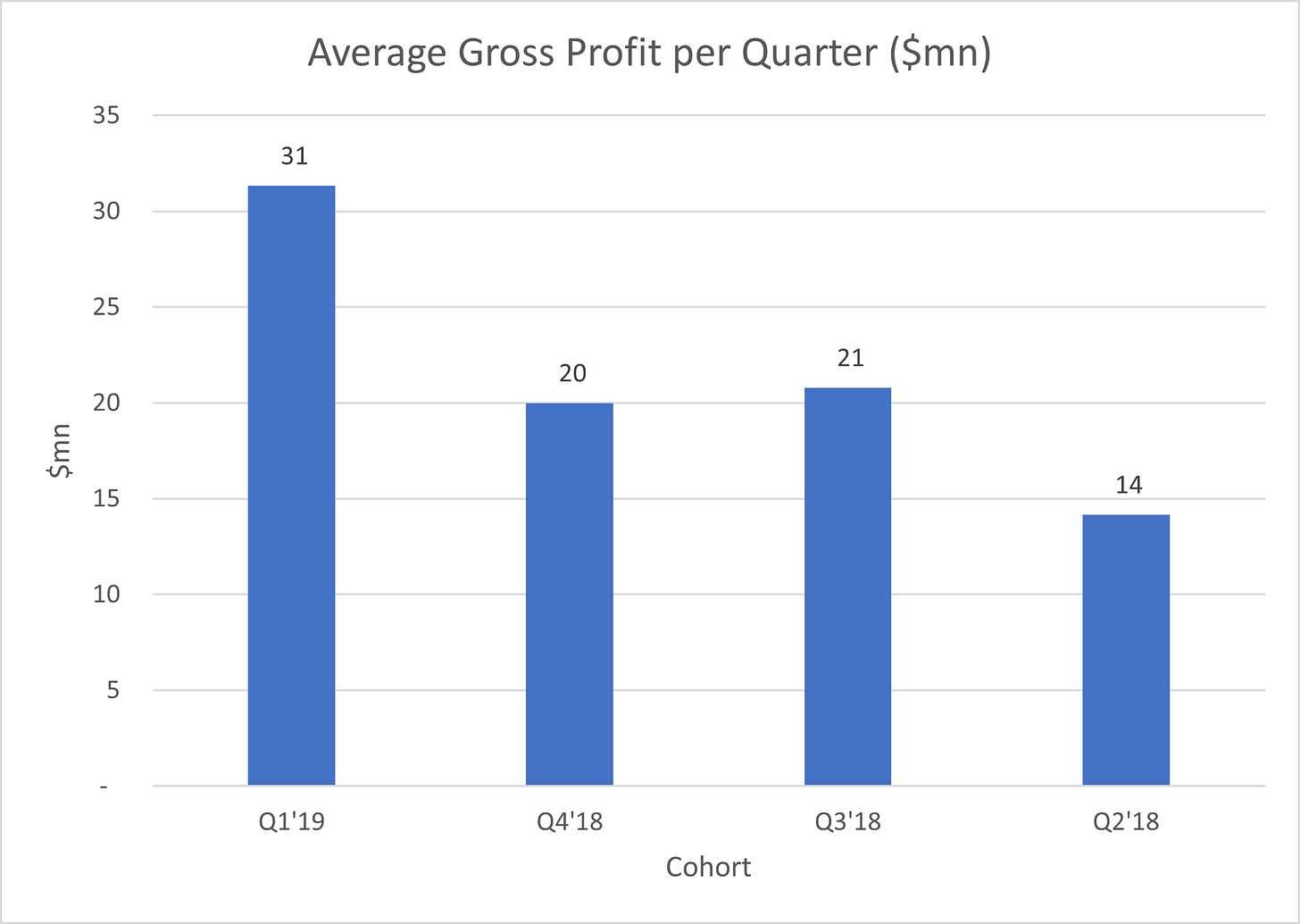

Analyzing the data in another way may reveal a different story. If we divide the cumulative gross profit by the number of quarters each of the same cohorts has contributed up till Q4 2019, it may paint a picture of decay. The oldest cohort, Q2 2018, contributes to an average of $14 million per quarter over six quarters, while the latest cohort (Q1 2019) contributes $31 million on average over three. You could argue that newer cohorts are spending more. Or more ominously, older cohorts spend considerably less (or none) over time, bringing the averages down.

Judging from its declining profitability and recent layoffs, the latter is more likely. Stitch Fix has not updated this data since Q4 2019.

Trying to scale, when older cohorts are depleting, presents a serious challenge. Replenishing one’s wardrobe is not the same as retaining a subscription with Netflix. Cost per Fix is far greater, and clothing more discretionary (or fickle) in terms of amount as well as frequency. Stitch Fix appears to be filling a bucket that continues to leak.

Power of Habit and Shopping Experience – Limiting Impact on TAM

In The Power of Habit, Charles Duhigg illustrates the human psychology behind the existence of habits. Every habit comprises a cue, a routine and a reward.

When it comes to apparel, the routine of shopping is an ingrained habit of exercising personal choices. Gratification comes from wandering into a mall (or an online store), selecting items that one covets, before checking out in a physical or virtual cart. This is retail therapy. In particular, the selection process is key to that pleasure.

What personalized styling services like Stitch Fix are advocating, however, take much of that personal choice away, on the premise that their data science can do it better. They are trying to change the shopping habit, by delaying that gratification, and delivering a surprise at the end. This will not appeal to many people. The fashionistas and fast fashion fans, who account for majority of the apparel market, will prefer that instant reward of choice. While they may try out personalized styling services, they are unlikely to stick around. There is no fierce loyalty to Stitch Fix, since it is a service, not a brand with evocative attributes. Also, the idea of relinquishing personal apparel choices to an algorithm can prompt a degree of defensiveness, especially with those who pride themselves as having good tastes.

Consequently, Stitch Fix is left with people who do not enjoy the shopping experience and would rather outsource it. But how valuable are these customers? From the cohort analysis above, not very. Stitch Fix customers seem to be spending less over time, or disappearing altogether. People with inherent disinterests in shopping are not as valuable as the fashionistas and fast fashion fans, who can be relied upon to keep buying.

No Man’s Land

Fashion needs to excite and engage. Nike did wonders with Michael Jordan back in the 80s, and it continues to produce dividends to this day. For years, H&M has been collaborating with the hottest designers like Lanvin and Viktor&Rolf to remain part of the zeitgeist.

Buzz sells. Algorithm by itself does not. Nordstrom just shut down Trunk Club, after years of trying to turn it around. THE YES, another personalized styling service, has been sold to Pinterest, which is only keeping the technology and plans to sunset the THE YES app as well as website post merger. These demises may suggest that the apparel box business model in its current form may have existential challenges.

Stitch Fix offers convenience for people who are not so keen on shopping or clothes, but they are a limited breed with sporadic purchases. Venturing outside of this core demographic further dilutes the stickiness. Without offering any enticing collections, Stitch Fix does not appeal to mainstream shoppers either. It is a tough no-man’s land.

As for the stock, it is dwelling in similar ambivalence, being neither a high-growth brand nor a marketplace aggregator.

(Author is neither long nor short $SFIX)

Subscribe to Consume Your Own Tech Investing to receive a welcome email with the following:

Latest Top 10 conviction Consumer and Tech positions in my portfolio

3 book recommendations on investing, consumer and technology sectors

One article delivered into your inbox every Tuesday

Preview of upcoming articles

In addition, you will receive Subscriber-Only emails with updates to my portfolio convictions and latest recommendations on books to read.

Follow me on Twitter @ConsumeOwnTech